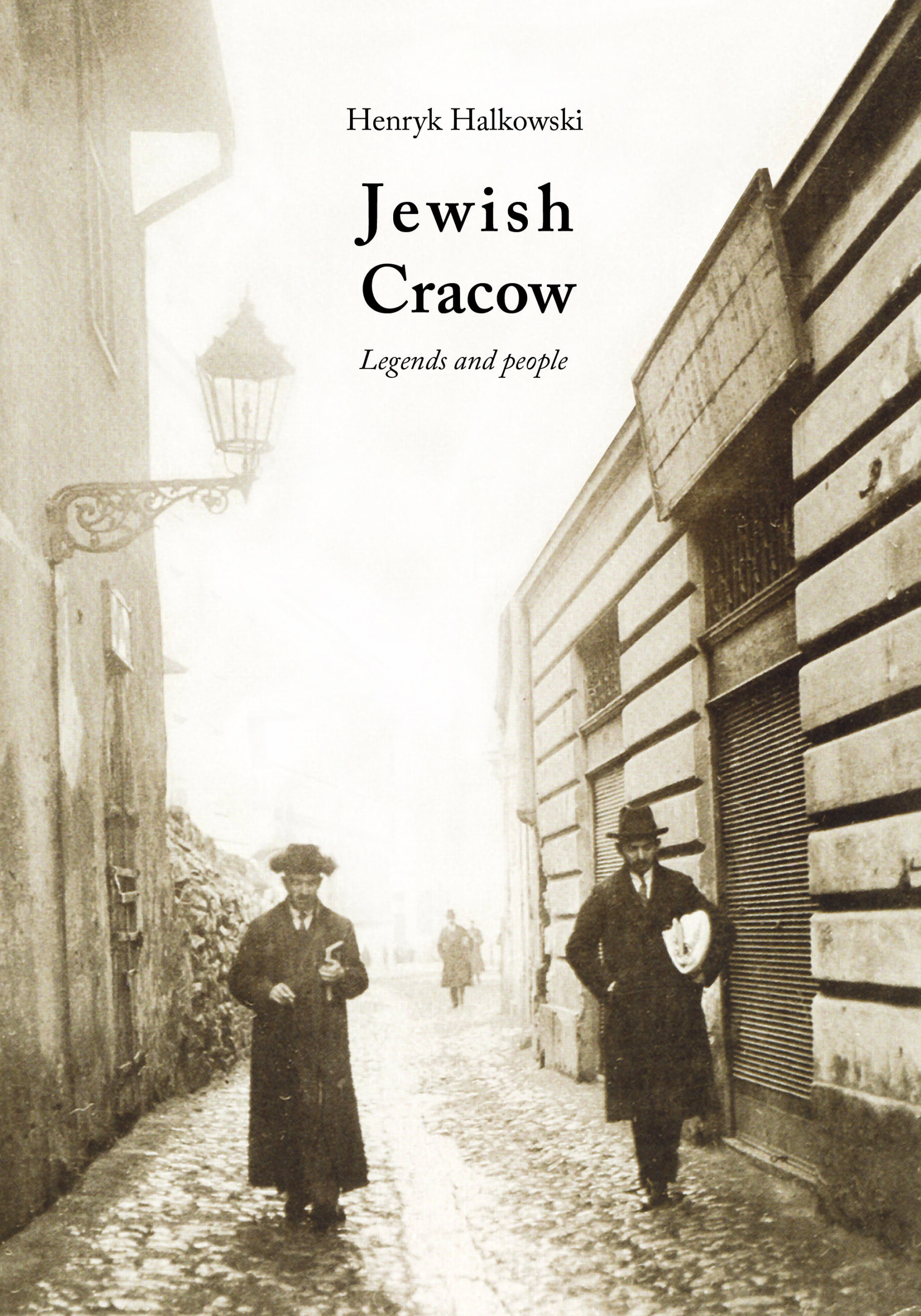

At the turn of the last century and this – and the last millennium and this (according to the non-Jewish calendar, of course) – I wrote the content and gathered the illustrations for a book that I wanted to call Jewish Kraków. History – legends – people – places. Circumstances at the time prevented me from having that book published, but the text of this book is largely based on the materials I prepared for it.

The void left by the Jews who were murdered in Poland during World War II or emigrated shortly afterwards is particularly palpable in the Kraków district of Kazimierz. The former Jewish quarter is always teeming with people, but essentially it is empty; its former residents are gone, not even their descendants are still here. And with them, the narrative that gave their lives meaning also evaporated.

Most tourists interested in Poland’s Jewish past visit three places: Oświęcim, Warsaw and Kraków. Oświęcim is the Auschwitz-Birkenau camp, aside from Jerusalem the place that has branded the Jewish consciousness more than any other. Warsaw is the ghetto, seen from the angle of the uprising (which in this perspective is the founding myth of the Israeli army and the State of Israel itself).

And Kraków? For centuries Jewish Kraków was one of the most important cities in the Jewish world. Home to some of Judaism’s most brilliant erudite minds, it was here, too, that the Ashkenazi identity – the identity of the Jews of Central and Eastern Europe – was formed. And yet Jewish Kraków sadly has no identity in most people’s consciousness. It is composed of empty houses, streets and squares with no narrative. There is a widespread conviction that the single greatest achievement of Kraków’s Jews in their more than 800-year history was graciously allowing themselves to be rescued by Oskar Schindler. And for this very reason, all that many people in the world know about Kraków is that it is a town, somewhere near Auschwitz and a salt mine, where the Good German Oskar Schindler saved some Jews (and where there are lots of bars and pubs for a good time).